Shares - Let's take a Closer Look

Shares - you know what they are, so let's see why people buy shares. It might sound trite, particularly when the stock market is crashing around people's ears, but over the long term shares are a good investment.

The figures are there to prove it. Pension funds might be looking for alternatives to shares such as government bonds and property, but even they know that it would be stupid to ignore the stock market completely given its past record of outperforming other forms of investment.

There are also two distinct markets for shares. The primary market, which is created when shares are first issued.

And there is something called the secondary market, when already existing shares are bought and sold. The biggest share market by far is the latter.

It is also important to understand what fundamental part risk plays in the valuation of shares.

And why it may be safer and more profitable buying shares in larger companies rather than shares in small companies, which tend to be untested and very risky.

You'll agree there is a lot more to shares and share trading than first meets the eye and that is why it is important to take a closer look.

In this section:

You've set up your online account and are ready to go.

So what's it all about?

Why invest in the stock market when the cash might be safer in a high interest savings account?

Well, despite what you may have heard to the contrary, the stock market still outperforms most other forms of saving.

And until recently that included ploughing cash into property.

The researchers have found that shares have returned 7pc annually over the past 50 years compared with around 2pc for more traditional forms of saving.

BUT, and I can't stress this enough, the above is only true if you have a balanced share portfolio and you hold those shares over the long run - five to seven years say.

Doing that will iron out the up's and down's of the market - kinks such as the grand market correction of 2000 when stock market bubble burst.

'Ah,' I hear you cry. 'If stock market is such a canny investment, then why are the big pension funds moving their assets out of shares and into property and bonds?'

Good question.

As the market rollercoastered after 2000, it became apparent, belatedly some would say, that big pension funds should spread their risk.

That said, pension fund cash is still heavily invested in the London stock market.

But this rush into government bonds, or gilts as they are known, has come at a price.

The rate of interest received from bonds is now minuscule.

Companies generally issue shares to raise money.

That cash may be used to fund the business and expansion plans, or it may go to the founders as a payback for the risks they have taken setting up the company.

There are also other benefits. A stock market listing raises the profile of a firm, gives it easy access to new forms of funding, which might previously have been limited to a bank loan.

The market for new share capital is known as the primary market.

Unless of course you are buying shares at the outset when the company first lists on the stock market, then the primary market will be of little interest.

Usually you will be buying and selling shares that were issued years ago.

And as an investor you are probably buying to make a capital gain - that is you hope the investment will go up, not down. You may also want to earn some income from your investment, which we call a dividend.

The market for used shares is called the secondary market.

The one thing we have not talked about in great depth is the concept of risk.

Markets go up and down as we have seen with the crash of 1987 and the pricking of the stock market bubble in 2000.

But also know in the long run these undulations iron themselves out and the market trend is steadily upwards.

Shares in companies should come with a health warning. Usually, smaller, untested and growing firms present the the highest risk of failure.

But you can also enjoy the biggest rewards.

Take the example of Vodafone. A £1,000 investment in the little known spin-off from Racal is now estimated to be worth several million pound.

But the Vodafone's and Microsoft's of this world - that have grown from risky start up to dominate their particular industry - are few and far between.

It is also a rule of thumb that bluechip firms present a lower risk investment. But rewards will also be smaller - in capital growth terms at least. And there are still risks.

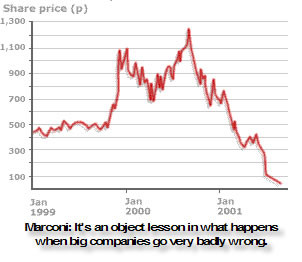

But a company called Marconi is, as they say, the exception that proves the rule.

Formerly the backbone of GEC, one of our biggest and best known industrial companies, it sold its crown jewel businesses and bet the cash on the internet revolution.

The net result - a catastrophic collapse in the share price when it turned out that its bosses had completely misjudged the growth of the market.

Massive debts meant the banks took control of Marconi and shareholders were left with a fraction of their investment.

Remember, this was a FTSE 100 company that at one point was valued at £35bn.

The content of this site is copyright 2016 Financial Spread Betting Ltd. Please contact us if you wish to reproduce any of it.