It’s January, so let’s talk about the January Effect.

But which January Effect would that be?

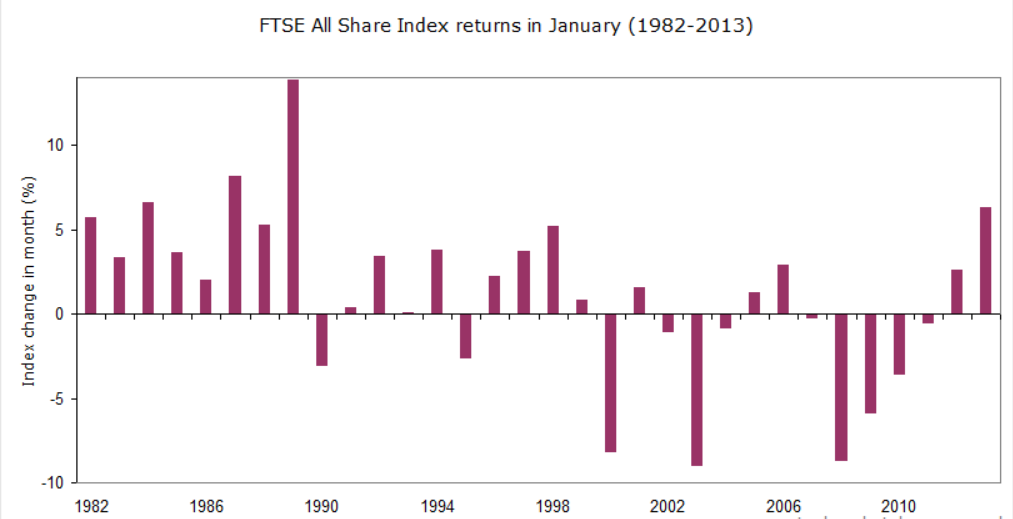

The January Effect refers to the tendency of small cap stocks to out-perform large-cap stocks in the month of January. However, the term January Effect is used rather loosely to also refer to stocks generally being strong in the first month of the year, and also to how the direction of the market in January forecasts the market direction of the whole year (this latter effect is also termed the January Barometer).

Mid-cap and small-cap stocks tend to out-perform large cap stocks in this month (called the January Effect)

Let’s explain the three different uses of the term in greater detail.

1. Small-caps out-perform large caps in January

The most common use of the term January Effect describes the tendency of small-cap stocks to out-perform large-cap stocks in January.

In 1976 an academic paper found that equally weighted indices of all the stocks on the NYSE had significantly higher returns in January than in the other 11 months during 1904-1974. This indicated that small capitalisation stocks out-performed larger stocks in January. Over the following years many further papers were written confirming this finding. In 2006 a paper tested this effect on data from 1802 and found the effect was consistent up to the present time.

The UK market experiences the same January Effect as seen in the US market. The small cap out-performance in January is significantly strong: the FTSE Small Cap Index has out-performed the FTSE 100 Index by an average 2.4 percentage points in all Januaries since year 2000. And the small cap index has under-performed the FTSE 100 Index in just one year in the past 13.

January follows the strongest two-week period of the year (the second half of December); and this exuberance traditionally carries over into the first few days of January as the market continues to climb for the first couple of days. But by around the fourth trading day the exhilaration is wearing off and the market then falls for the next two weeks – the second week of January has been the weakest week for the market in the whole year. Then, around the middle of the third week, the market has tended to rebound sharply.

Small caps like January

Mid-cap and small-cap stocks tend to out-perform large cap stocks in this month (called the January Effect). On average, since 2000 the FTSE 250 Index has outperformed the FTSE 100 by 2.3 percentage points in January – the best out-performance (with February) of all months. Small caps do even better, out-performing the FTSE 100 by an average 3.7 percentage points in the first month.

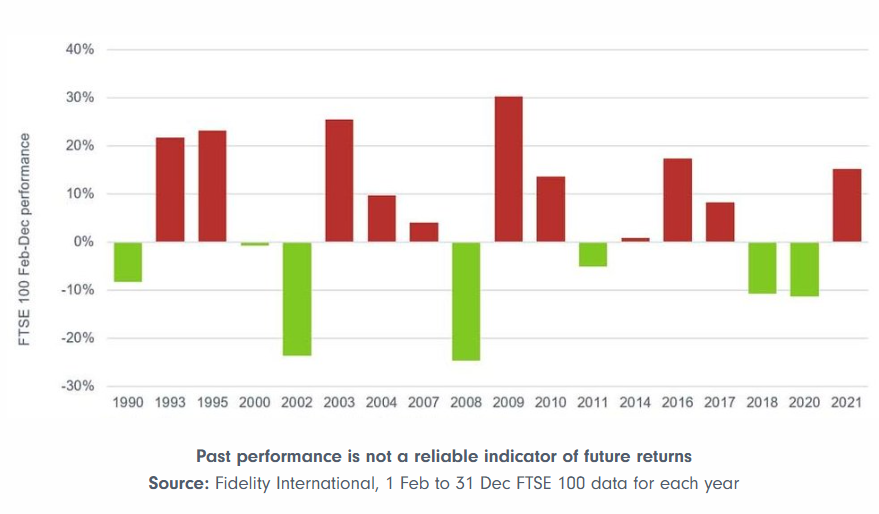

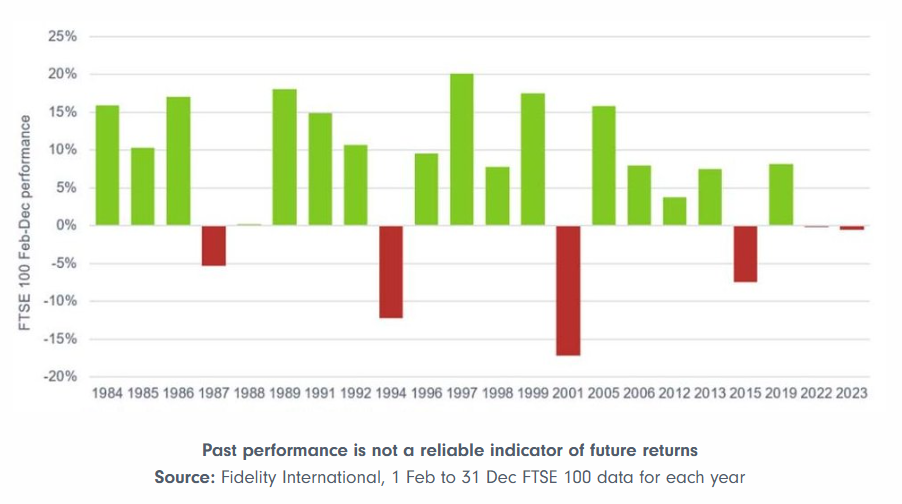

2. January predicts the market for rest of the year

Historically, the returns in January have signaled the returns for the rest of the year. If January market returns are positive, then returns for the whole year have tended to be positive (and vice versa).

This is sometimes called the other January effect, or January Predictor or January Barometer and was first mentioned by Yale Hirsch of the Stock Traders Almanac in 1972. A variant of this effect has it that returns for the whole year can be predicted by the direction of the market in just the first five days of the year.

The findings reveal that out of 22 instances where the Index gained in January, it delivered a positive return for the rest of the year on 16 occasions. Promising results so far.

Years with a positive FTSE 100 in January

Green signifies when the January effect worked, red when not

The barometer was less reliable when the Index declined in January. Of the 18 instances where this occurred, the Index produced a negative return for the remainder of the year only seven times, while it gained on the other 11 occasions.

Years with a negative FTSE 100 in January

Analyzing these results suggests that the January barometer has been accurate 23 times over the 40-year history of the FTSE 100, equating to just over half the time.

In recent years, the January barometer’s performance has been notably lackluster. The last instance of its accuracy was in 2020, when a sharp decline in January foreshadowed an even larger drop for the year overall.

Research shows that the same rule works more or less for the UK market as well.

Academic research has largely found that January returns can predict the rest of the year, but there is some doubt as to whether the effect can be exploited.

And Dan Greenhaus of BTIG points out that January is not necessarily any better a predictor of full year performance than any other month. According to him,

When February is down, the 12 month return inclusive of that February is 2.0%. When February is up, the S&P 500 returns 12.53% and similar for the other months.

3. The market tends to rise in January

In 1942 Sidney B. Wachtel wrote a paper, “Certain Observations on Seasonal Movements in Stock Prices”, in which he proposed that stocks rose in January as investors began buying again after the year-end tax-induced sell-off.

The January Effect is like this seasonal quirk where stock prices supposedly jump in January. Why? The theory goes that at the end of December, people sell off bad-performing stocks to get tax breaks, and then in January, they buy them back. This demand pushes prices up.

While this has been noticed in places like the U.S., it’s not clear if it happens everywhere – especially in markets like the UK. The idea of the ‘January Effect’ is pretty simple: stocks supposedly do better in January than in other months. Sounds like free money, right? But recent research looking at the UK stock market from 2009 to 2020 throws some curveballs at this idea. Let’s break it down.

What Did the Study Find?

A group of researchers took a hard look at UK stocks (specifically the FTSE 100 Index) over 11 years. They crunched the numbers to see if this January thing holds up. Here’s what they found:

- Not Much Action in January:

- Turns out, January returns in the UK aren’t all that special. Sure, sometimes they’re a bit higher, but nothing statistically mind-blowing.

- It’s More About May and June:

- The real action seems to be in May and June. Why? The UK’s tax year ends in April, so it’s likely that investors are making moves after that, not in January.

- Tax-Loss Selling? Not Really:

- Unlike the U.S., where the tax year matches the calendar year, the UK tax year ending in April makes the January Effect less of a thing. It just doesn’t fit.

What Does This Mean for You?

Here’s what you can take away:

- Don’t Obsess Over January: If you’re looking to trade on seasonal trends, maybe check out May and June instead.

- Know Your Market: Stuff like tax rules and local market quirks matter. What works in the U.S. might not fly in the UK.

- Don’t Bet the Farm: These patterns are cool to know about, but they’re not a guaranteed win. Costs and other factors can kill the edge.

Key Observations:

- Small Cap Outperformance: Small caps generally outperform larger indices in January.

- Variability: January returns and their impact vary significantly year-to-year, highlighting the difficulty of relying on the January Effect as a predictive tool.

Has the January Effect Faded Over Time?

While the study above provides valuable insights, it is limited to the UK market. Future research could expand the analysis to other developed and emerging economies, examining how local factors influence calendar effects. Additionally, a longer data period might capture broader trends and cyclical changes.

The January Effect is a phenomenon with a long history. In 1976, researchers Rozeff and Kinney found that, from 1904 to 1974, the average monthly return in January was 3.5%, compared to just 0.5% for other months. The reasons behind this disparity were largely speculative. Historically, the rise in US share prices in January was attributed to factors such as tax-loss harvesting in December—where investors sell losing stocks to offset gains—workers investing their bonuses in January, and fund managers buying well-performing stocks from the previous year to make their portfolios appear more attractive. Another plausible explanation is the optimism that often accompanies the New Year. Resolutions to plan for the future might prompt individuals to start investing or increase their contributions. Researchers also noted that the January Effect was more pronounced in smaller-cap stocks.

However, modern analysis suggests that the January Effect may have diminished in significance. Data covering the period from late 1986 to December 2017 indicates that January has become a relatively average performer, delivering middling results in both UK and US markets.

Conclusion

The term January Effect encompasses multiple phenomena:

- Small-cap stocks outperforming large caps.

- January returns signaling the market’s direction for the year.

- A tendency for stock prices to rise in January.

The January Effect might sound like a cheat code for making money, but in the UK, it’s not that simple. If you want to stay ahead, you’ve got to understand the market you’re playing in. Keep learning, keep analyzing, and don’t let the hype fool you.