Why Analysts as a Group are Always Wrong

Feb 28, 2013 at 2:29 pm in Fundamental Analysis by Dave

The more regular readers amongst you will know that I hold a lot of participants in the financial markets industry in extremely low regard. This is not without reason or experience however.

Having been a former fund manager, stockbroker and, horror of horrors, an “anal”yst myself, I have had first-hand experience of dealing with a lot of these individuals. How many of them would I trust to manage a single penny of my money? Yup, you guessed it, none. And, incidentally, this is part of the reason as to why we are launching our new company- Titan Investment Partners will offer all the benefits of professional fund management but, uniquely, within a spread betting wrapper.

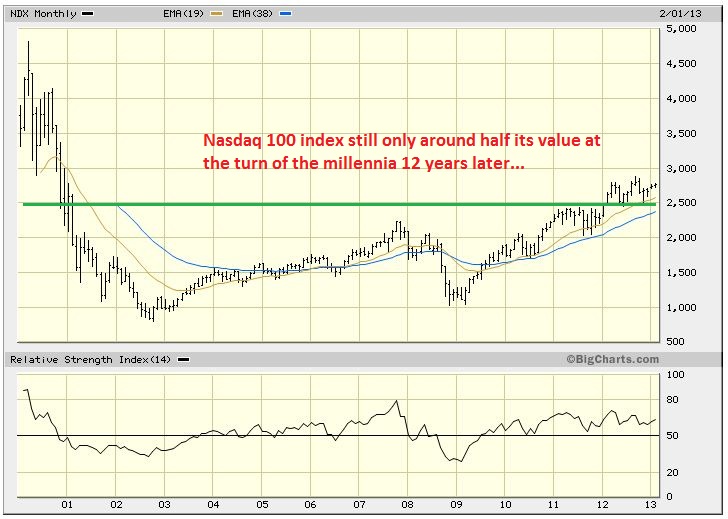

In recent years, there have been some major market dislocations – at the turn of the century with the dotcom bubble – an event that, some 13 years later, the Nasdaq still has not recovered from (see chart below) and more recently the subprime crisis that engulfed the entire globe in 2008-09. How many of these highly paid industry professionals saw these dislocations coming? An exceptionally small number as you will see… It is interesting to me that around the turn of the millennium the few lone dissenters were in fact experienced ‘old timers’ – individuals who had been around the block and could see that we were in fact in a bubble. It was the younger analysts and fund managers who were caught up in the hype & were blind-sided by the euphoric extremes and had no experience of a bear market, having cut their teeth in the boom years of the 90s in which stock markets seemed to only go one way – up.

Dr Doom

One particular analyst with whom I had a great deal of sympathy at the time was a chap who came to be known as “Dr Doom” given his bearish views — Mr Tony Dye former CIO of what was then known as Phillips & Drew (and now simply UBS).

I never got the chance to meet him as a fund manager, but I was aware of his cracking track record and his value bias of investment. Unfortunately for Mr Dye, his logical views and ability to realise that stocks were wildly overvalued was ironically his downfall. During 1999, as stock markets continued to inflate and particularly in the technology arena, he came under increasing pressure from his clients and fellow management to explain just why he was underperforming so badly. At the end of 1999 his firm was ranked 66th out of 67 for performance. Dye’s answer to his critics was simply that the market was overvalued and he didn’t want to succumb to the “bigger fool” bandwagon, particularly as the months rolled by and he may just in fact, if capitulating, be the bigger fool!

Mr Dye resigned just after the market crashed and he was ultimately vindicated as stock markets around the globe halved through to 2003. Dye started a new fund management company and went on to produce, once more, exceptional returns for his clients before sadly passing away in 2008. To me, he was a true fund manager — a man who made money through thick and thin, who stuck to his disciplines and investment beliefs and not someone who was in the right place at the right time like many of the so called “hot shot” fund managers of recent years.

Empirical Evidence of the Collective Uselessness of Analysts as a Group

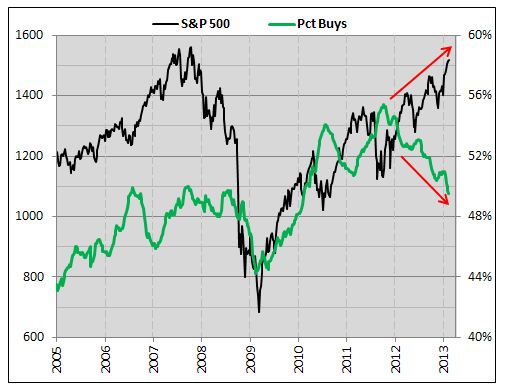

Below is a chart that depicts the percentage of analysts who rated US Stocks, in aggregate, as a Buy during the last 5 years and overlaid on this is the S&P 500 itself. Notice anything in particular? Two major observations stand out to me — firstly, the green line is a lagging and NOT a leading indicator. This means that analysts are just reacting to the market and not anticipating which is what they are paid to do — anticipate and thus add value.

Secondly, we can see that at the nadirs of the bear market in early 2009, they had the fewest number of buys in recent history. Think about that for a moment — at precisely the point where these highly paid individuals should be anticipating that valuations were at historic lows and that the downside was minimal, they were similarly so shaken with fear, it seems that they simply could not see the wood for the trees.

In short, analysts as a group in supposedly the most efficient market in the world — the US — have absolutely no predictive power, and in fact are, ironically, only of value as a contrarian signal!

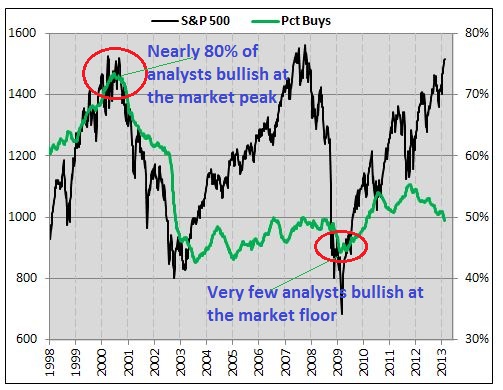

We are not finished yet in presenting the evidence to the collective “jury” that is the investment marketplace however. An even more damning dataset is presented in all its glory below which looks back at their collective predictive power over 15 years. Spot a pattern? What we should be seeing is a peak in analysts Buy recommendations as the market hits a nadir, and a low in such recommendations at the peak. And yet, the historical record portrays precisely the opposite.

Group-Think

Let’s look at some of the reasons behind this major value destruction that they collectively create within the marketplace. That vast majority of analysts are in their 20s and 30s and so: (a) simply do not have the experience of an elongated market cycle; (b) the investment industry is entirely about personal nest feathering, in many cases at the expense of the actual investor, and so there is “safety in numbers”. In other words, if you are a recent graduate taking your place on an analyst team at an investment bank and consensus amongst your peers is blithe positivity about a particular stock, why be a hero and go out on a limb? Best case you make a name for yourself but perhaps upset management of that company and so cut your firm off from lucrative corporate fees; worst case you are too early in your call, still cut the firm off from corporate fees and you lose your job.

The other major reason why they are so wrong is quite simply due to what is called “anchoring”. Management of companies put out guidance to the marketplace and the vast majority of analysts simply plug these figures into their spreadsheets. With the “herding” mentality we explained above, then those analysts who are not close to the company simply congregate around this figure. This is ‘group-think’ and humans are hard wired to conform to this.

How to Profit from their Collective Uselessness

If we know just how useless analysts are, then the question, of course, is how do we use this information to profit?

Here’s my shortlist of what I look for in a short position:

- Relatively low short interest from stock borrowing data implying that should a company slip up with its results or the market face a correction, then heavy short covering will not act as a buying support for the stock.

- Consensus media positivity – pretty much for all the reasons detailed here – it is very rare that a journalist will swim against the tide and put his own neck on the block (present publication excepted of course!) in making a contrarian call.

- Almost universal positivity amongst analysts covering the stock, with very few sell recommendations. Where there is a sell recommendation, and it is produced by an independent research house, then the bear arguments are pored over carefully.

- The first thing I look at in an analyst note is the disclaimer at the bottom of the note in which they are legally forced to disclose if they have, or expect to, receive fees from the company in question, generally due to corporate finance fees. This tells me all I need to know about independence and objectivity.

- I personally never, ever, ever follow a Goldman Sachs Buy note and would likely do the opposite of what they recommend. Nuff said on that one.

Vice versa is true on the buy side: i.e. what I look for in deciding, as part of my investment process, whether to purchase a stock are the following:

1. You’ll be surprised perhaps to hear that it is not actually universal negativity around a company. Recall my point about analysts not, in general, being “heroes” with ballsy calls. Well, if a stock is universally hated, then there is usually a very glaring fundamental reason for this such as a declining marketplace, debt problems etc.

What I like to see is neutral consensus sentiment with a strong bull and bear argument by one or two analysts and the bull argument from an entirely independent analyst, i.e. not connected to the company. The neutral basis tells me that the company is probably forgotten and surprises are not expected by the investment community. Again, it is the smaller research boutiques that generally produce the dissenting calls and whose clients are hedge funds prepared to pay for good research. A buy argument that is well reasoned is part of my cue for action.

2. Large short positions in the marketplace such that positive news can act as a catalyst for the stock and which then receives extra buying fuel through short covering.

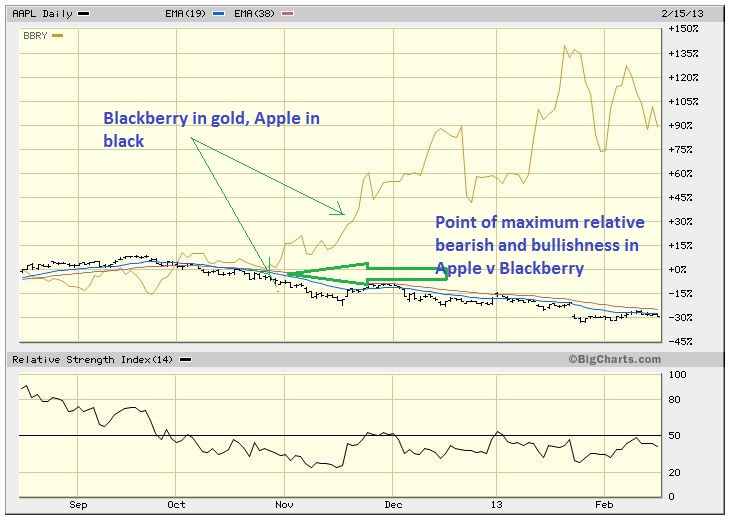

Two companies display in perfect graphical form the points above. Shoring up the bear side is Apple: a stock that fitted all the criteria detailed here – universal positive sentiment, few sell recommendations; and on the bull side – a stock with heavy short interest and where very few analysts were buyers – Blackberry (formerly known as Research in Motion). They say a picture speaks a thousand words – take a look at the 6 month relative chart below.

One other point that comes out of this analysis is that anybody who still believes in EMH – Efficient Market Hypothesis – is either a prime example of the saying “there’s none so blind as them that can’t see” or just plain dumb. EMH states that a stock price at a point in time is an accurate reflection of all known and unknown information (i.e. it also reflects insider positioning) and so it is, by default, unless you are lucky, impossible to outperform the market. I would argue that the market that is comprised primarily of investment professionals is so biased in their views and riddled with conflicts, that if we can recognise this and know when to go against the grain that precisely this collective inefficiency is our opportunity.

Article reproduced from the March 2013 edition of Spread Betting eMagazine