The Worst Stock Market Crashes of the last Century – Part II

Jan 4, 2013 at 8:45 pm in Fundamental Analysis by Dave

Last month, we kicked off the first of two articles looking back over the major stock market shakeouts of the last 100 years. We started by analysing two sets of panic (the Panic of 1901 and the Panic of 1907) both of which resulted from failed attempts to corner a market in the early 1900’s and which ultimately resulted in heavy sell offs that destroyed many fortunes and kicked off periods of recession.

The liquidity problems that resulted from those particular panics led, in fact, to the creation in 1913 of the anchor of the global monetary system that is known as the Federal Reserve System in the hope of avoiding such situations in the future. On this count, I think it’s safe to say the Fed has failed miserably, and regularly!

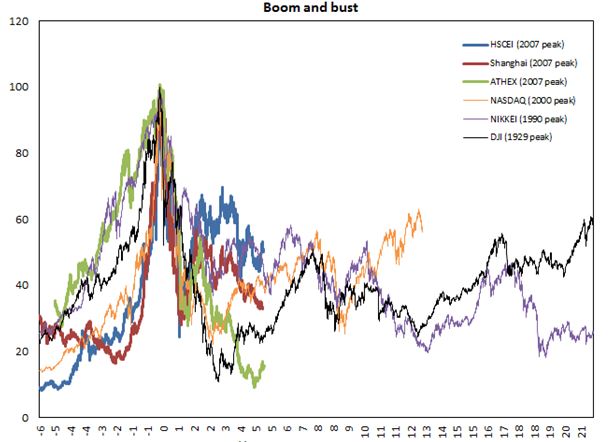

In 1929, a series of events led to what is known as the “Granddaddy” of all crashes — The Great Crash of 1929 in the US. The Great Crash resulted in very heavy capital losses that metamorphosed into a long and deep depression, akin to the situation Greece is presently facing, and which gave way to an unemployment rate in the States of almost 30%. Quite unbelievably, at its nadirs, the Dow Jones index fell to less than 10% of its pre-crash value. Nothing like it in development markets has been since, although in developing markets the Asia currency crisis in 1997 led, in dollar terms, to 80-90% capital losses in the equity markets and similarly in countries like Greek and Cyprus in the last few years. Below is a chart showing how various global markets have charted a path in the aftermath of these monster bouts of capital destruction:

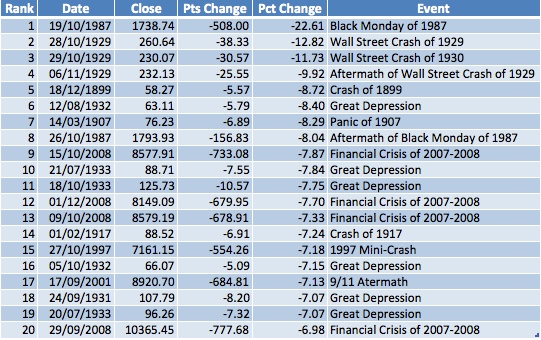

In 1987, another historically important crash occurred that became known as “Black Monday”, where the major global markets including the US & UK fell by over 20%. Lessons from the past, however, helped in avoiding a major recession as the global central bankers of the day used serious monetary stimuli to contain most of the negative effects of an asset price shock.

In this magazine edition we will conclude with the Friday the 13th mini-crash of 1989, the October 27, 1997 mini-crash, the 9/11 aftermath crash of 2001, the 2008 Great Financial Crisis crash, and finally the curious phenomenon of the 2010 flash crash.

The Friday the 13th Mini-Crash of 1989

Although this crash seems minor when seen today, it is important in the context of this piece to analyse it as it highlights two problems that we still need to fight against today: the excessive dependence on computer trading, particularly more so with the growth in so called “high frequency, algo” trading, and the age old human psychology element of blithely following the crowd…

On the morning of the superstitiously “spooky” October 13th, 1989, the market suddenly turned down on very heavy volume. At the close, the Dow showed a 6.91% loss while the S&P 500 dropped 6.12% leaving many traders scratching their heads as to just what the catalyst was.

Many commentators believe that the trigger for the drop was actually a failed leveraged bailout deal whereby UAL Corporation was attempting to acquire United Airlines. The deal was bunkered when the Association of Flight Attendants (AFA) voted against accepting the proposed deal which was backed by management. Consequently, the $6.9 billion deal collapsed and with it the whole market.

The problem is that this reasoning doesn’t stand up to closer scrutiny, as the market actually started dropping before the breakdown of the deal. Again, a lot of market commentators blamed automatic selling by computers as one of the main causes that led to the large drop, as in the 1989 crash.

Two lessons to learn: first, sometimes it is required to just halt the market to allow traders to get some fresh air and clear their thoughts — hence the introduction in later years of so called “circuit breakers”. Secondly, the pre-programmed strategies of multitude computers to sell on declines could be disastrous. The first warning was in 1987. This was the second…

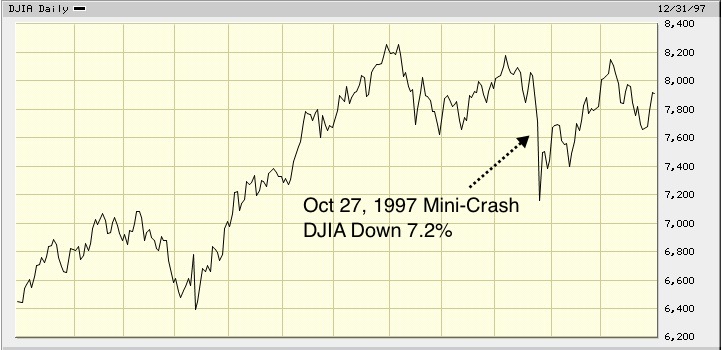

October 27, 1997 Mini-Crash

The crash occurring on October 27, 1997 is probably one of the least known in recent years, but it had its origin in the Asian currency crisis and carried out many a professional fund manager operating in that region.

The day certainly didn’t start well in Asia with the Hang Seng index alone dropping 6%. Nerves got the better of traders in the region with continued worries over the regional property market and the collapsing of domestic currencies. The Western economies were, however, able to avoid the worst of the crisis as their exposure to the bad loans of the all but bankrupt regional banks in Asia was minimal. Still, the mini-crash that occurred on that day led all global markets substantially lower. In New York, the NYSE was halted twice to avoid continuing panic selling, but the loss at the end of the day still amounted to a serious 7.2%.

During the following sessions, the Hang Seng Index continued the drop but this was not followed by US markets and, in the end, the Dow Jones ended the year with a 22.6% gain and the event was seemingly swiftly forgotten.

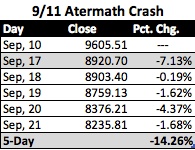

9/11 Twin Towers Aftermath Crash

The biggest difference between this particular crash and the others is that in the immediate aftermath of the atrocities, people knew what was coming in the markets. The terrorist attacks occurred on the morning of September 11, 2001, just before the markets actually opened in New York, and such was the devastation and confusion that a decision was taken by the NYSE officials to keep the markets closed. This meant that overseas markets, and in particular Europe, took the brunt of selling that the US fund managers were unable to implement in their home market. Over the course of a few days, UK & European markets lost around 20%.

The US markets re-opened on Monday, September 17 and it was very evident that a crash would occur. In the initial event, the drop was remarkably contained in the US, considering how much overseas markets had tumbled. The Dow closed down 684.81 points on the Monday, corresponding to a loss in value of 7.13%. The losses did, however, extend over the balance of the week and the Dow accumulated a decline of 14% over five consecutive negative sessions. Airlines and insurers were heavy losers on September 14. United Airlines and American Airlines, two of the airlines used by the terrorists in the attack, saw the shares drop 40%. Global air traffic declined considerably over the following months which led to a decline in revenues and profits amongst the global airline industry and ultimately to the bankruptcy of US Airways and United Airlines, and also massive layoffs at American Airlines

One intriguing element of the 9/11 crash is that there was “suspicious” and very heavy activity in airline and index Puts in the days leading up to the attacks. Somebody made hundreds of millions on these bets and, to this day, the culprits still seem to remain in the shadows. This only adds weight to the conspiracy theorists’ stories that many more people knew what was coming on that terrible day than is widely believed.

9/11 Aftermath

The attacks on the Twin Towers shocked the world and set the geo political stage for the adventures by the UK & US into the Iraqi & Afghanistan theatres. The markets grappled with the implications for many months in the immediate aftermath of Sep 11. One particular compounding issue that led to the markets making decade lows almost a year later was the fact the world economy was still coming through the effects of the bursting of the end millennia technology bubble and the devastating wealth decimation that occurred in this arena. A final bottom was made in April 2003 — ironically just around the time of the Invasion of Iraq.

A few lessons here — anticipation of a crash and selling elsewhere, as in Europe in the days after the Sep 11 attacks, generally means that the worst will not come to pass as “those who want out are out”. Two, as occurred in April 2003, once valuations reach historic nadirs, news flow can become an obscuring factor and inherent value becomes more important. Many would have been forgiven for expecting the first shots in Iraq to set off another downturn in the markets, but, in the event, this marked the low point for a strong 4 year bull run. The old adage “Buy when blood is on the streets” rings true more often than not.

The recession of 2002-03 may not be attributed directly to the terrorist attacks, but, still, Bin Laden’s attacks had far reaching consequences that, one could argue, have now culminated in the fiscal cliff we see being debated 10 years later. George “dubya” Bush initiated a so called “war on terror” and in the process substantially expanded the defense budget to fight in Iraq & Afghanistan and to protect the country against future attacks. This spending frenzy has most certainly contributed to the current high levels of national debt the U.S. currently hold, and that is at the heart of the fiscal cliff issue.

2008 Great Financial Crisis Crash

If we use the common definition of a crash, then, strictly speaking, the “GFC”, as it is known, wouldn’t fit the category of a large, very short term decline. It really belongs more to the bear market definition than to a market crash. In fact, in recent years, a 7% or 8% drop in a day is becoming more commonplace than it was in the first half of the last century. This is in spite of the likes of “circuit breakers” being introduced. Nevertheless, there are four declines which occurred during the 2008 financial crisis that make it into the top 20 Dow declines and with that in mind we include them here.

The 2008 financial crisis was one of the worst economic slumps to affect the globe for over 80 years. The economic shocks quickly spread throughout the whole world and put Europe & the US in serious trouble. Even today, some 5 years later, global interest rates remain at record lows.

As a result of the GFC, the US housing sector slumped by record levels once venerable banks had to go “cap in hand” to their governments for bailouts, and seemingly impenetrable financial institutions like Lehman Brothers collapsed. The origins of the crisis lay within the US housing market and the improper evaluation of risk, coupled with plain human greed.

During the nineties and noughties, the U.S. current account deficits just kept on growing, leading the country to borrow ever large sums from abroad — particularly China which was desperately trying to recycle the mirror of the US’s export deficit — their own massive current account surpluses. As yields continued to fall during the seemingly never ending bond market bull run, investors began to search for yield elsewhere, and so financial institutions expanded credit to U.S. households and consumers who in turn assumed an unprecedented debt load (mortgages, auto credit, credit cards, etc).

With the housing market in the US appearing to be on a path of ever greater prosperity, the mortgage banks embraced the sub-prime sector of the market in their search for returns and credit risk just went out of the window. Put simply, an event of default was just ignored.

With so much interest in the housing market, financial institutions created a way of selling a section of the market to investors through what are called mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralised debt obligations (CDO’s). The bonds were split into safe and not so safe tranches and, of course, whilst everything was appearing to be going swimmingly, nobody looked too closely at what was actually included in these pools of bonds…

Unfortunately, what goes up also generally comes down and the US housing market started to crack in 2007. With this decline, the MBS securities dropped in value and, given the leverage that many of the investment banks had taken on with regards to holding these assets on their balance sheets, they became technically insolvent. Consequently, banks tightened credit conditions, the housing market continued its collapse and foreclosures grew exponentially. The financial meltdown was now in full swing.

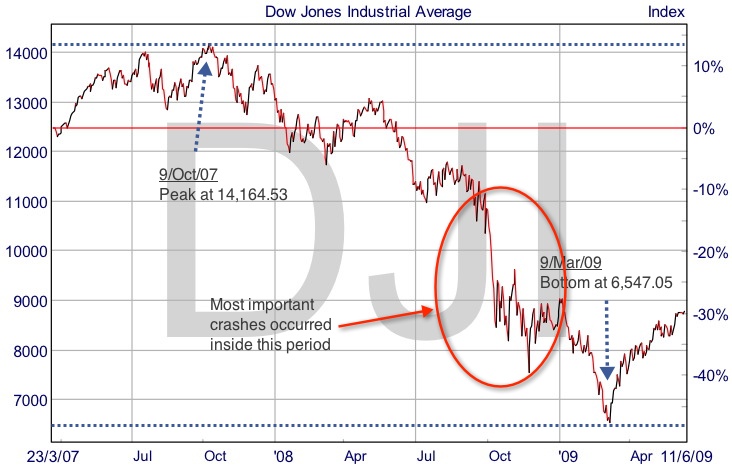

When the GFC finally ended in March 2009, the Dow had dropped 54% from a peak at 14,164 to its final bottom at 6,547 in just 17 months. In just 8 weeks, between September 29 and December 1, 2008 there were four “crashes” that gained a place in the top 20 list. The first was on September 29, when the Dow declined 777.68 points, or 6.98%. The second slump on October 9, erased 678.91 points from the index — corresponding to a percentage loss of 7.33%. A few days later, on October 15, the Dow lost another 733.08 points, or 7.87%, and, finally, on December 1, the index suffered the fourth substantial loss amounting to 679.95 points, or 7.7%.

The 2010 Flash Crash

The 2010 “flash crash” occurred on the afternoon of May 6 and came, quite literally, out of nowhere. To this day, the main reason behind it is still argued over. If the necessary steps had been taken in the aftermath of the 1987 and 1989 crashes, however, the 2010 crash could have been avoided. The continued growth in computer trading and its automation quite simply exacerbated the fall and so the same risks still remain.

With the advent of computerised trading, a good proportion of the traditional “market maker” role is now disappearing and pre-programmed computers take decisions based on complex algorithms. Instead of the human trader placing dozens of trades a day, computers are programmed for high-frequency trading (HFT), holding shares for less than a few seconds in many cases whilst trying to exploit infinitesimally small pricing anomalies.

On the morning of May 6 2011, traders woke up to fresh news coming out of Greece and sentiment was poor. The Dow opened in the red, initially dropping little more than 2%. A mutual fund then decided to sell a large number of E-mini S&P 500 contracts in the futures market in order to hedge an equity position they had. Although the orders were placed in a way to avoid disturbing the market, some selling pressure was obviously created. With a broad negative market sentiment, the HFT’s started selling aggressively, quickly passing positions back and forth to exploit the perceived opportunity and, in the process, massively contributing to the amplified selling pressure. With the eroding market conditions the HFT’s then stopped trading, but panic selling continued. Other institutional investors using complex algorithms added to the blood bath.

In just a few short minutes, the Dow stood down more than 9% and it seems that sensibility kicked in as real “human” traders shut off the autopilot and assumed the manual commands to drive the market higher again with the index recovering almost all the losses by the close.

In an investigation, the SEC blamed the mutual fund that triggered the order for the sharp shakedown, instead of acknowledging that computers were responsible for the scary episode and that new measures should be taken to at least create longer time scaled circuit breakers to protect retail investors. Shares of global companies like Accenture and Exelon dropped to just one cent, and Procter & Gamble declined 37%.

Although the markets managed to quickly recover, many retail investors with leveraged accounts certainly saw their funds vanish.

Conclusion

Crashes have been a part of markets since they were created — wherever human emotions are concerned — and with the pendulum of greed and fear, and self enrichment thrown into the mix then they will continue to occur.

At the beginning of the last century, several attempts to corner a particular market were the main driver for these crashes and, in a lot of instances, resulted in a bear market due to the absence of a “firewall” able to provide the necessary liquidity to stop the downfall. Most of these episodes were preceded by an extensive bull market that resulted in a bubble being formed.

Over the last half of the 20th century, the increased processing power of computers has changed everything. The speed with which news is disseminated is resulting in ever more of these episodes.

With the exception of the GFC, unlike what happened in the 1901, 1907, or 1929 crashes, the most recent episodes haven’t resulted in recessions as the global “backstop” of the US Federal Reserve rides to the rescue with new liquidity injections. The snag is: the Fed’s now out of bullets — sovereign debt requires a major reigning in and so fiscal levers will not be available in response to a new episode — interest rates have hit the zero bound and QE’s power is now definitely waning with bond yields so low — the incremental “hit” of each injection of new cash being progressively more limited.

The lesson? When (not if) the next one hits, it probably will be the “big one”!

Article reproduced from the January edition of Spread Betting eMagazine