What is a Whipsaw Loss?

May 5, 2012 at 8:11 pm in Trading Mistakes by

You may have heard the term ‘whipsaw loss’ but you may be at something of a loss as to what it means. It means a loss that you suffer when you’re trying to enter a position and your newly-opened position stops out at a loss because the price goes the wrong way. And you try again, and you get stopped out yet again at a loss, because the price ‘whipsaws’ back and forth.

Whipsaw Loss Example

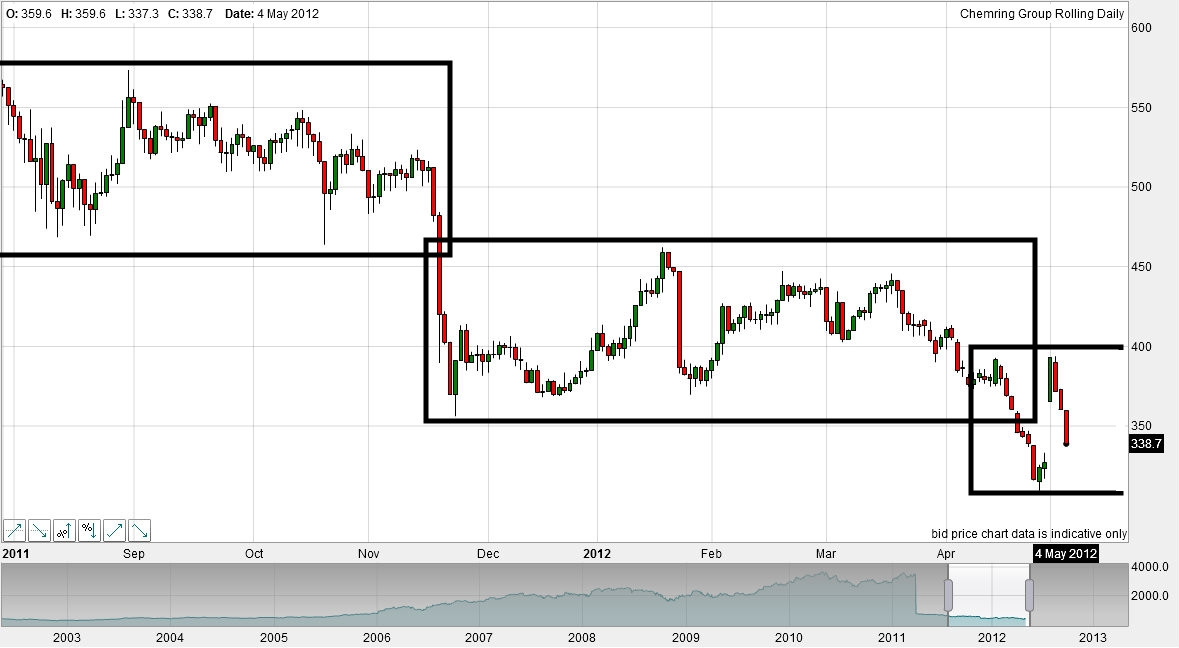

In the chart that follows, having witnessed the price of this stock bounce along a potential support level at about 368p (trust me if you can’t see the price) and then fall below it, the trader might reasonably assume that this ex-support level would become a new resistance level. Why? Because that’s what sometimes happens, and it fits in with the Darvas Box Theory.

In the belief that if the price ever rose back up to the ex-support level / now assumed resistance level, it would begin to fall back again, imagine that at the end of this chart the trader placed a limit order to sell on the SUPPORT / RESISTANCE SELL LINE (indicated) at 368p. And imagine that this trader was clever enough to apply a protective stop order to buy at 378p in case he got it wrong, thereby accepting a risk of just £10 on a £1-per-point nominal bet.

The following chart shows that the subsequently the price did rise to the supposed resistance level of 368, thus selling him into a short position, but it kept on rising so that he almost immediately stopped out at 378 for the loss of £10. After rising some more, the price began to fall back towards the stop-out price thus proving to the trader that his original hypothesis was right. So he sold again, at about the same price as his last stop-out price and with another risk-to-stop of £10. The price rose again (of course), thereby causing this trader to suffer another £10 “whipsaw loss”. At this point he gave up all hope, only to see the price fall back far enough to prove his original hypothesis to have been correct all along!

With the benefit of our perfect hindsight we shouldn’t gloat, and ‘I’ can’t gloat because it was one of my own failed trades.

What went wrong?

In one sense ‘nothing all all’ went wrong because the original hypothesis was proved correct, and because in the meantime the stop orders did their job. The trader (yes, it was me) should not have re-sold out of fear of “missing out” on the original trade. But on the other hand, re-selling for a third time would have paid off in the end.

Anyway, the moral of this sorry story is that the two £10 losses that were incurred when the trade went the wrong way, then went the right way, and then went the wrong way again, are what we call ‘whipsaw losses’. And it’s the reason that I once vowed to simply let a failed trade go and to sit out the next loss until an opportunity arose to sell (in this case) again at an even better price. Which I could have done, if only I’d followed my own advice.

The other possible remedy would have been not to have applied such tight stop orders in the first place, so as not to get stopped out for those whipsaw losses; thereby allowing the price more leeway to go the wrong way before it went the right way. But how do we know when we’re right (yet the market doesn’t realise it) and when we’re plain wrong?

Maybe all we can hope for is to take those whipsaw losses on the chin, in the expectation that we’ll be right more times than we are wrong or will at least make more money whenever we are right.

Back to the Darvas Drawing Board

If I go back to the Darvas drawing board and overlay some boxes, we can see that the result looks like this:

The first transition from one box to another was pretty perfect, with the old support level becoming a pretty firm resistance level. The second transition — the one that led to the whipsaw losses — was not so convincing, with the third and final box overlapping the second one.

I call the third box the ‘final’ box because when the boxes begin to overlap I take it as a sign that the longer-term trend may be coming to an end. I might turn out to be right about that, but if this article demonstrates anything it’s the fact that you can lose money even when you turn out to have been right.

Tony Loton is a private trader, and author of the book “Stop Orders” published by Harriman House.